Ask the question.

And hold fast, no matter what might be ahead.

If you have ever walked into a meeting only to find that a previously done deal is undone — with a new course of action that feels muddy and not based on the accepted facts — you know what an off-kilter frame is. The goalposts have moved, new data has emerged, someone is making a power play, etc. This is the time to invoke the guts of the strategic plan. Start a conversation that ties the new course of action to everything from the organization’s purpose to the OKRs and KPIs. If the shift in action actually changes the course set by the strategy, ask how the action will serve the strategic priorities, which objective it serves, and how the organization will measure and know the objective is being fulfilled. This helps everyone in the room understand whether the change — however it was conceived and now being directed — is relevant to the strategy. You might learn that it is, even if the change was manufactured outside of the established process. Keep asking until you get a direct answer — or as we know from using artificial intelligence, keep prompting. You might get blank stares and out-of-meeting maneuvers later, but at least you are contributing — you are focusing on facts and not flights of potentially ambitious fancy. By establishing the action’s relevance to the established strategy, you pull a potentially rogue action back into the process. Next: advocate to get it codified into the strategic plan, so it can be measured out in the open; then update the plan. Using strategy in this way, you invite the entire room to collaborate in the daylight, and even if stuff continues to happen outside the process, you build a habit of pulling it back into the process. And: you contribute not just to the ongoing relevance of the strategy but to the sustenance of a real team effort. You are honoring the strategic process, not to mention your sense of order. And possibly your sense of integrity.

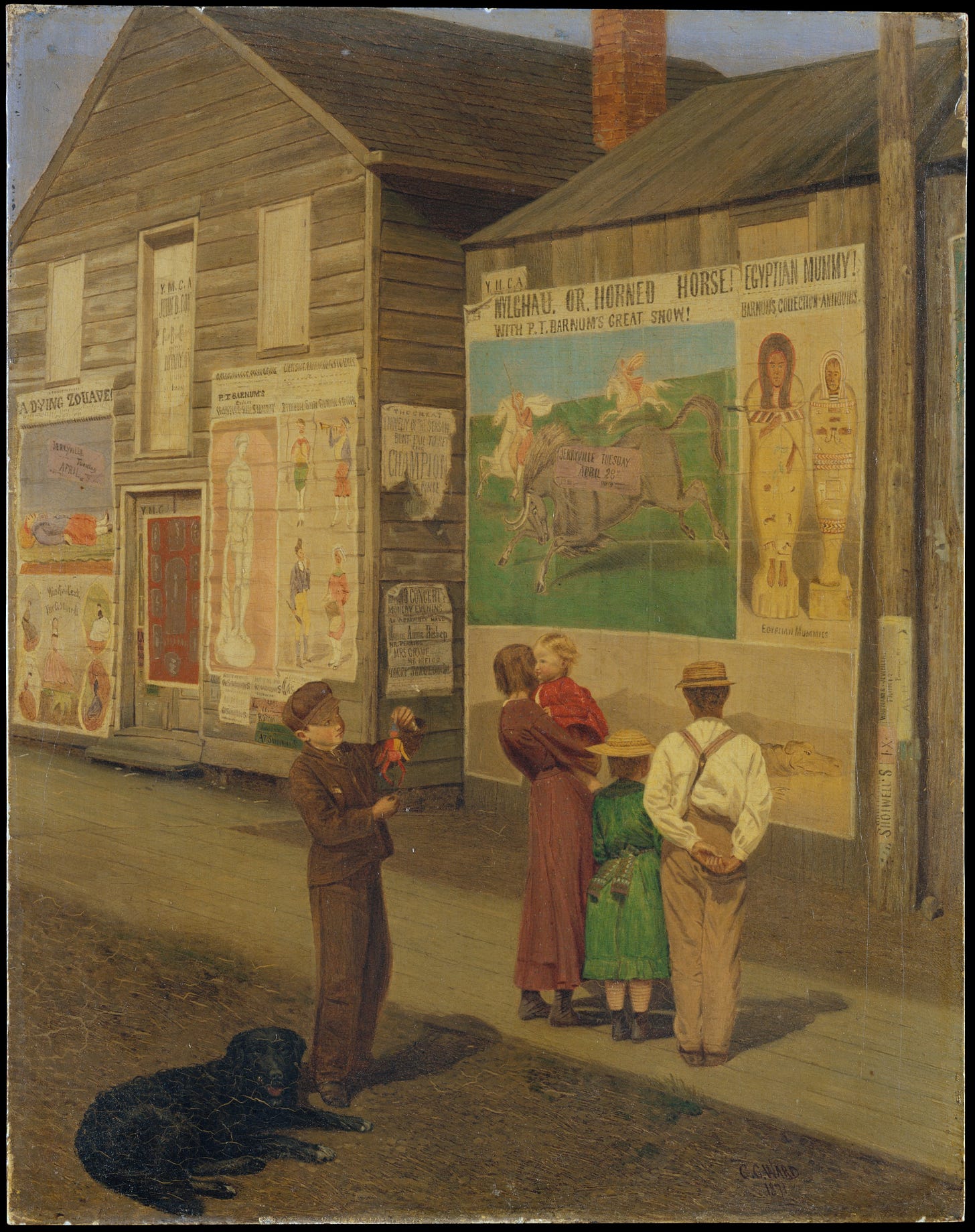

Coming Events Cast Their Shadow Before. Charles Caleb Ward. 1871. Oil on wood. Bequest of Susan Vanderpoel Clark, 1967. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When the question — not the answer — is the mistake

Aaron de Smet and Tim Koller: The framing effect is a well-documented cognitive bias in which people with identical information make different decisions based on how the information is presented. Research by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman showed that the way a problem is presented can heavily influence the options people consider and the decisions they make. Additional studies have shown that groups are just as susceptible to the framing effect as individuals, particularly in high-stakes or uncertain situations. A frequent consequence of the framing effect is asking misguided questions. In business settings, framing an issue too narrowly or embedding unchallenged assumptions often leads teams to ask the wrong question. The right questions are crucial as generative AI and agentic AI assume central roles in the workplace, because these tools will confidently generate or act on whatever they’re given, even if the original framing is flawed.

A leader’s roadmap to enterprise governance and AI training for employees

Alaura Weaver: Start with simple steps before taking on complex AI systems. Use a step-by-step plan to guide your organization from basic assistive tools to advanced AI agents, making sure the process is manageable and focuses on a good return on investment.

Lochiel’s Warning

Thomas Campbell: 'Tis the sunset of life gives me mystical lore, And coming events cast their shadow before.